BBC News 6 November 2020

Democrat Joe Biden has a path to victory in the US election but his Republican opponent President Donald Trump is challenging vote counts in four key states. So what might happen?

What are the challenges issued by Trump?

Wisconsin

The president's campaign has said it will request a recount in Wisconsin "based on abnormalities seen" on election day.

It's unclear when this recount would take place, however, since typically these do not happen until after the county officials finish reviewing the votes. The state's deadline for this part of the process is 17 November.

Columbia University Law School professor Richard Briffault says there was a recount in Wisconsin in 2016 as well, and it "changed about a hundred votes".

"A recount is not a means of, challenging the legality of a vote," he explains. "It's just about literally a means of making sure that the calculations are right."

Michigan

Mr Trump won the state in 2016 by his slimmest margin - just over 10,700 votes. On 4 November, his campaign announced a lawsuit to stop the count there over absentee ballot handling, though 96% of the votes have already been unofficially tallied by local election officials.

On 5 November, a judge dismissed the lawsuit, saying it was filed too late and the campaign failed to make its case.

Pennsylvania

The challenge here centres on the state's decision to count ballots that are postmarked by Election Day but arrive up to three days late. Republicans are seeking an appeal.

Matthew Weil, director of the Bipartisan Policy Research Center's elections project, says he is most concerned about this dispute as the nation's top court was deadlocked on it before the election - and before Justice Amy Coney Barrett joined.

"They did indicate in some of their dissents that they would be interested in taking it after. So I do think there is a risk that some of those [postal] ballots that were cast by election day and not received until Friday may be discarded. I think that would be the wrong result, but I think that is a legally possible result."

But Weil adds that the election would have to be "very, very close for that to matter". He points out that state officials had sent out messaging ahead of election day urging voters to turn in their absentee ballots at polling places instead of posting them. "So my guess is that it's not going to be a huge number of ballots that could be thrown out, if that was the case."

Prof Briffault also points out that the ballots arriving late are being counted separately, and says if Mr Biden can pull ahead without those being tallied, he sees no basis for a legal challenge.

But the Trump campaign has declared victory in the state though there are more than a million votes still to be tallied. No major US networks have yet projected a winner.

Georgia

State Republicans and Mr Trump's campaign also filed a lawsuit in Georgia's Chatham County to pause the count, alleging problems with absentee ballot processing.

Georgia Republican chairman David Shafer tweeted that party observers saw a woman "mix over 50 ballots into the stack of uncounted absentee ballots".

On 5 November, a judge dismissed this lawsuit, saying there was "no evidence" of improper ballot mixing.

Could anything reach the Supreme Court?

Early Wednesday, Mr Trump also claimed voting fraud without evidence, and added: "We'll be going to the US Supreme Court - we want all voting to stop."

Voting has already stopped - polls closed on Election Day, though there is the question of late ballots, like in Pennsylvania.

Mr Weil says: "The Supreme Court doesn't have any kind of special power to stop the legal counting process."

Prof Briffault also says that campaigns may dispute close contests in pivotal states, but "they still nonetheless have to have [a case] that raises a constitutional concern" for it to reach the Supreme Court.

"There's no standard process for bringing election disputes to the Supreme Court. It's very unusual and it would have to involve a very significant issue."

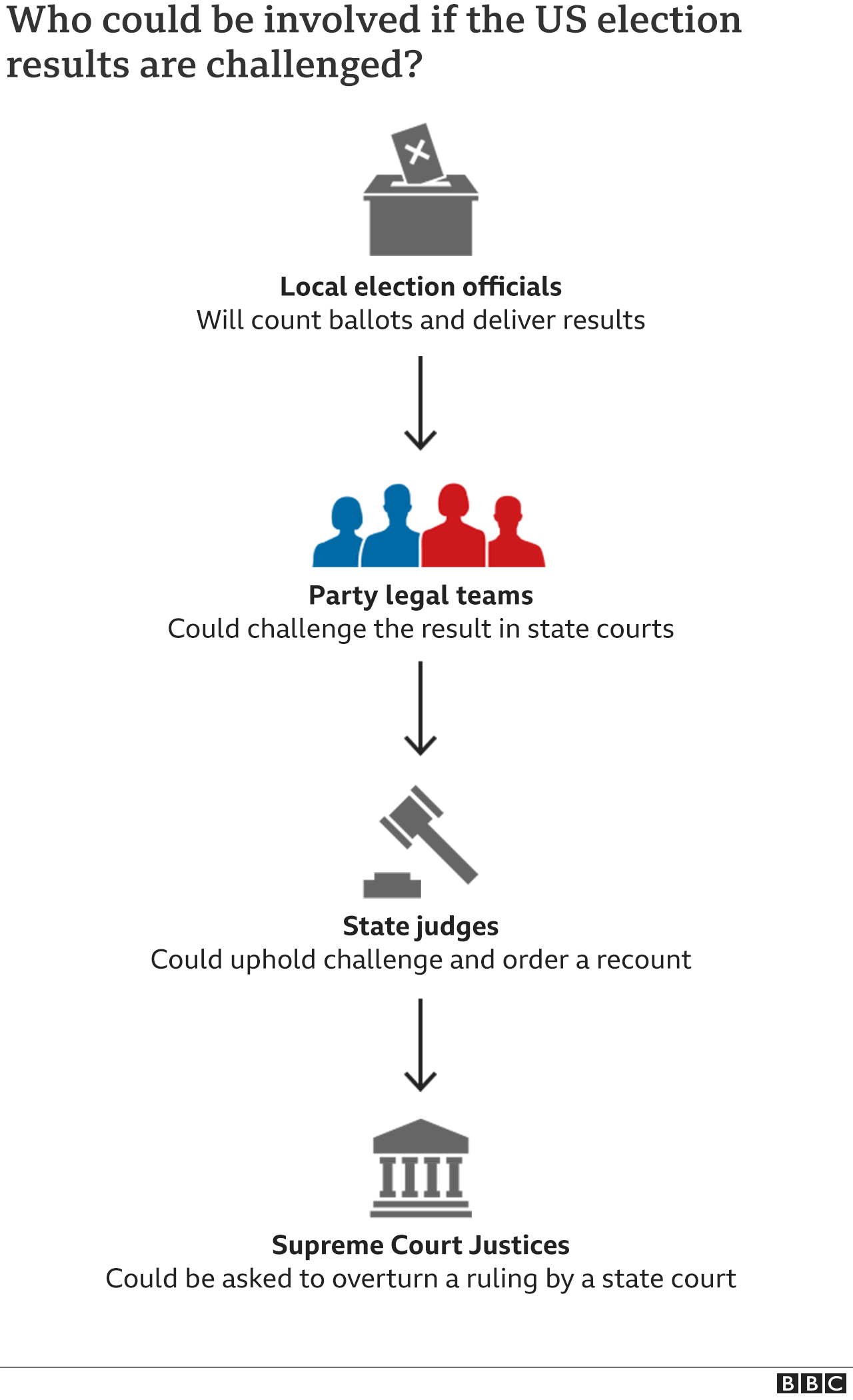

If the election result is challenged, it would require legal teams to challenge the result in the state courts. State judges would then need to uphold the challenge and order a recount, and Supreme Court justices could then be asked to overturn a ruling.

In some places, recounts are automatically triggered if the margins are close enough - you may remember Florida's in the 2000 presidential election between George W Bush and Al Gore (more on that below).

Shouldn't we know the results by now?

Yes and no. Usually, when the data shows a candidate has an unbeatable lead, the major US networks declare one candidate the winner. This tends to happen in the early hours of the morning after voting day.

These are not official, final results - they are projections, and the final official tally has always taken days to count.

But this year's massive volume of postal votes means the counting is taking longer, especially as some battleground states have not allowed counting ahead of election day.

So they have had to count everything on the day itself, and counting postal votes can take longer than in-person votes due to verification requirements.

If races are too close to call, and neither candidate concedes, it's normal for the counting to go on, says Mr Weil.

There were obstacles before voting

It was already a very litigious election.

Before Tuesday's vote, there were more than 300 lawsuits across 44 states regarding postal and early voting in elections this year.

They centred on a range of issues such as the deadline for posting and receiving ballots, the witness signatures required and the envelopes used to post them.

Republican-run states said restrictions were necessary to clamp down on voter fraud.

But Democrats said these were attempts to keep people from exercising their civic rights.

How long can this drag on?

Because this is a presidential race, there are key federal and constitutional deadlines to move things along:

- States have about five weeks from 3 November to figure out which candidate won their presidential contest. This is called the "safe harbour" deadline, and this year, it's 8 December.

- If states haven't settled on their electors by this date - remember the president is chosen by an electoral college not the popular vote - Congress can rule that their electors won't count in the final tally.

- On 14 December, electors meet in their respective states to vote.

- If we still don't have a majority-winner after 6 January, then Congress decides the outcome in what's called a contingent election.

- The House of Representatives will select the president while the Senate confirms the vice-president. Yes, this means we could see a president and vice-president from different parties, but maybe don't prep your Biden-Pence signs just yet.

- Each House state delegation gets one vote. Whoever wins 26 delegations is the new US president.

But Mr Weil notes that "a lot would have to go wrong to get to this situation where the House and Senate are really deciding the presidency". Namely, the election would need to be incredibly close.

"It's not just that some states have to be up for grabs," he says. "We could have some disagreements in states and still have one candidate getting to 270 electoral college votes."

Why might states not declare a winner?

What if the states themselves can't agree on who gets their electors? You could imagine this happening if one party argues that the final vote count is inaccurate or rigged.

The key battlegrounds of North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin all currently have split governments - Democratic governors but Republican-majority legislatures.

In a contested election, lawmakers could theoretically split from their governors and submit their own certified electors to Congress. (This happened in 1876 - but more on that below.)

Congress would need to determine whose votes count - the ones submitted by the legislature or the governor's.

If the House and Senate both agree, there's no problem. If they're split, we're in uncharted waters, though some experts say federal law is in favour of the governor's electors.

The final, final deadline

No matter what, on 20 January, the Constitution says there must be a new presidential term.

"At noon, we have to swear in somebody to be president. If there isn't an outcome, then we go into our succession plan," Mr Weil says.

Mr Weil notes we could also see a scenario where the House is in a deadlock about the president, but the Senate confirms a vice-presidential pick.

If the House can't resolve it by Inauguration Day, the Senate-selected vice-president becomes the president.

Next in line, if there's no vice-president - the Speaker of the House (currently a Democrat, Nancy Pelosi).

Have we seen this kind of drama before?

To date, the 2000 election this is the only one decided by the Supreme Court, when George Bush edged out Al Gore.

It was a tight race between Democrat Mr Gore and Republican Mr Bush. On election day, Gore won the popular vote, but things were closer in the electoral college. Everything hinged on how Florida doled out its 25 electoral votes.

The race was close enough to trigger a recount. Mr Gore's team asked for four counties to do that recount by hand, prompting an appeal by the Bush camp. Weeks later, the Supreme Court ruled in favour of Bush along party lines 5-4. Mr Gore conceded and President Bush moved into the White House.

There are two other instances of unusual outcomes:

Right to the wire, 1876

Lawmakers had another election mess on their hands in 1876, between Democrat Samuel Tilden and Republican Rutherford Hayes. Tilden was one vote short of a win in the electoral college. Four states had electoral disputes - and if Hayes won those, he'd win it all.

Lawmakers appointed a bi-partisan commission to decide the winner. And so came the Compromise of 1877: Hayes won - by a margin of one electoral vote - by negotiating with southern Democrats. The election was resolved just two days before Inauguration Day.

Getting most electoral college votes still not enough, 1824

In 1824, the man who won the popular vote and the most electoral college votes did not win the election.

Andrew Jackson appeared to narrowly beat John Quincy Adams for the sixth presidential seat, but because neither candidate secured a majority, the decision went, per the Constitution, to the House.

The Speaker at the time, Henry Clay, was not a Jackson fan. In what's known as the "corrupt bargain", Clay negotiated with House lawmakers and Adams to secure the win for Adams - and the Secretary of State role for himself.

Reporting by Ritu Prasad

0 Comments:

Yorum Gönder